On August 21st, 1870 aboard the whaleship Sunbeam, two-time whaler Silliman Ives found himself ill with a condition “very akin to mumps, with the exception of the swelling”. It prevented him from opening his mouth, and he dreamt of the days when such an action was possible.

“I never really appreciated the luxury of a good gape before. When a fellow cannot open his mouth to any greater extent than the width of a lead pencil, gaping is not a success to say the least. And then anything in the way of a sneeze is entirely out of the question, unless you are prepared to part company with the top of your head at very short notice. A ship is a hard place to be unwell in. So long as one is in good health you can get along nicely. But if you are sick the only place where you can find sympathy is in the dictionary. And then too the remedies at hand are limited in number and obsolete in use. Your medicine chest is filled with medicines in use a hundred years ago, but which modern pharmacy has dispensed with to a very great extent. Calomel and castor oil and such like delectable doses. There is no question about it. A whale ship ought to have a surgeon, and the law should oblige such vessels to carry them. When I get into Congress I shall introduce a “Bill” to that effect.”

As Mr. Ives noted, American whaleships went without doctors aboard even when the work was rife with injury and illness, and often quite far from access to any kind of care ashore. On British whalers it was required by law for a surgeon to be signed on for the voyage—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was one on a voyage bound for the Arctic and apparently fell in the water so many times that the crew called him the 'Great Northern Diver'. However on American whalers—which dominated the industry—a doctor was seen by the agents as an unnecessary expense. There was the captain, the carpenter, and folks who could mend sails. Together, that makes one whole doctor! Right?

Read on, to see how they fare.

An 1845 whalers medicine chest with vials of medicine labeled with numbers, and a lower drawer with plasters, a tourniquet, and pliers in it. From the collection of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Joan Druett, in her book Rough Medicine highlighted some really fascinating things that came as a result of this, ranging from men who had scars that healed in a herringbone pattern because they were mended like canvas, to this wild tale about an amputation performed between a captain and mate at gunpoint:

“Another stirring tale told is of a Captain Coffin, who was hurt so badly in a whaling accident that it was obvious his leg would have to go. Being the master, the medic, and the patient all at once, he knew the situation was complicated, but he was more than equal to the task. He sent for his pistol and a knife, saying to his mate, “Now, sir, you gotta lop off this here leg, and if you flinch—well, sir, you get shot in the head.” Then he sat as steady as a rock while the mate went at it with the knife, holding the pistol unwaveringly until the operation was completed. No sooner was the stump wrapped up and the leg cast overboard than both men fainted.”

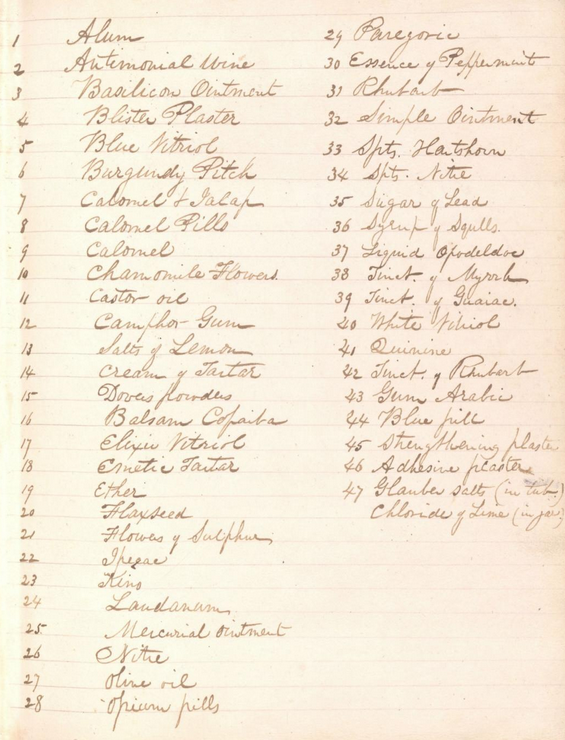

It was the captain's responsibility to provide medical care. Often without training himself, he was given a medicine chest full of numbered tinctures for various treatments. Those tinctures were a mix of chemical and herbal compounds, some which are still used holistically today and some that you.....absolutely want nowhere near your body. Epsom salts as a laxative, laudanum for painkiller, St John's wort for bruises and burns, mercury for syphilis, rosemary as an antiseptic, lead acetate as an anti-inflammatory, arrowroot for dysentery, henbane for insomnia, and on it goes from the innocuous to the dangerous.

John B King was a rare doctor aboard a whaleship, sailing on the Aurora out of Nantucket in 1837. He wasn’t hired as a doctor though; for reasons unknown he initially obscured his identity and joined simply as a foremasthand until his skills were revealed and he became the ship’s doctor. On that voyage he kept a book of the medicines he used.

John King’s medicine list, from the collections of the Nantucket Historical Association.

In addition to dosing medicine, the captain would also be responsible for setting broken bones. Benjamin Boodry, who had been whaling since the age of 13 and by 1856 was captain of the Fanny described instances in which he had to tend to his crew.

“At 2 o clock a cask of watter rooled away in the Bluber room and one John Haggerty tryed to stop it and got his leg broke just above the Nee there was another chance to show my surgical skill set it splinted it and bandaged it.”

“McKee fel from the Main Topsail yard on deck bled him in both arms he came to some broke his arm and leg and badly bruised”.

Fortunately for McKee, his accident happened off the coast of Faial. The captain sent for a doctor ashore to examine him. He was advised to leave McKee in the Azores where he could receive more proper rest and treatment. But if land was a long way off, people had to make do the best they could.

Some captains had a better bedside manner than others. Where Silliman Ives felt terribly neglected in his illness, William Abbe of the Atkins Adams, 1859, had quite a different experience. He turned to the captain for help with a painful swelling on his hand that eventually grew so bad he was unable to use it.

“The captain was extremely tender in his treatment of my hand, pouring on laudanum to relieve the pain, lancing with caution and as tenderly as could he and using every means in his power to make me comfortable—washing my hand thrice a day with warm water and cutting away dead skin, pressing out matter in a manner that gained my affection + respect. Mrs. Wilson sent me preserved meats, pickled oysters, cake, buttered bread and seconded her husband in all his care. I felt a great deal of respect for both these kind people + shall repay it when I can […] The Cap treated us all with a care + skill that surprised me — I supposed that we should be left to take care of ourselves—the case in many ships, but we were not only cared for but allowed to stay below until we thought fit to return to duty.”

Mrs. Wilson—the captain’s wife—stepping up to help was not so unusual. Often whaling wives also found themselves taking on the role of doctor. All throughout July 1846, Mary Brewster was busy tending to the ailments of the crew aboard the Tiger.

“The last part of the day I have spent in making doses for the sick, in dressing some hands and feet, 5 sick and I am sent to for all the medicin. I am willing to do what can be done for any one particularly if sick for in whaling season a whaleship is a hard place for comfort for well ones and much more sick men.”

She reported that all her patients recovered, with the exception of a young man with a liver complaint beyond her immediate treatment.

Other times, other members of the crew served as de facto doctors as well. One such man was veteran whaler John Martin aboard the Lucy Ann 1842. In addition to being a skilled watercolorist, he also had a knack for bloodletting and tooth pulling. Often he made note of his ministrations in his journal:

“Blistered Frank on the side for his pleurisy & the steward on the neck for the sore throat”

“Cupped the steward on the back of his neck with wine glasses and lanced with razor for want of proper instruments, which gave him almost instant relief”

“Pulled a large jaw tooth for one of the crew. I lanced the gum with a penknife & set him spouting thick blood, & at the second wrench of the iron turned it up.” [Very cheeky language he’s using here, the same sort of talk one uses when hunting whales]

“The loose whale struck Mr. Dean on the lower jaw & broke it, & knocked out 2 of his lower teeth, & he was taken on board [...] Sat up with Mr. Dean last night [...] Bled Mr. Dean [...] Drew 3 teeth from Mr. Deans broken jaw.”

“Bled Antone. Since the death of Manuel, Antone has been on the sick list with swelled testicles and pain in his back. Poor fellow, he is very much frightened & thinks he is going to follow Manuel. He occupies the same bunk. When I bled him, he was so frightened that the perspiration stood on him in large drops, & groaned like a person dying.”

“Blistered and glystered [clystered, i.e. gave an enema] Antone.”

One of John Martin’s watercolors from his journal. NBWM.

Blistering, bleeding, and emetics were among the most common treatments for all that ailed a man aboard. John King included his recipe for creating a blistering plaster and its uses:

“Blisters are serviceable in affections of the chest attended with much pain and difficulty of breathing. Bleeding or purging is proper previous to the application. Severe and long-continued headaches are relieved by a blister to the back of the neck. In all cases before applying a blister, the part should be washed with warm vinegar and wiped dry. The plaster should be spread as thick as a wafer on soft leather. When laid aside it soon becomes mouldy in the dampness of a ship, but if rubbed over with a knife the same one will draw two or three times. When very old it loses its strength. From eight to twelve hours is the time usually required for drawing a blister. Then remove it and dress with basilicon or simple ointment”

—

Other ailments were met with more specific treatments. It was not uncommon to see logbooks noting several men laid low on account of ‘the venereal’.

William Chappell, a cooper and boatsteerer aboard the Saratoga in the early 1850s commented on the frequency the mate found himself off duty following liberty ashore.

“Our mate is off duty again with that disgracefull disease and as near as I can find out it threatens destruction to a small but very usefull member of the body I am sorry for him but he is old enough to know better than to play with every body that looks pretty and bewitching”

“Flaxseed tea is very serviceable in clap”, wrote John King in his journal, as well as white vitriol “sometimes used as an injection in protracted cases of clap.” For syphilis, the common treatments were more severe. King writes,

“No 25. Mercurial Ointment

This is frequently used in venereal cases for bringing the system under the influence of mercury. The bulk of a small nutmeg is rubbed on the inside of the thighs morning and evening until the gums are slightly sore. It is a good application to chancres when mixed with twice the quantity of lard, and renewed twice a day.”

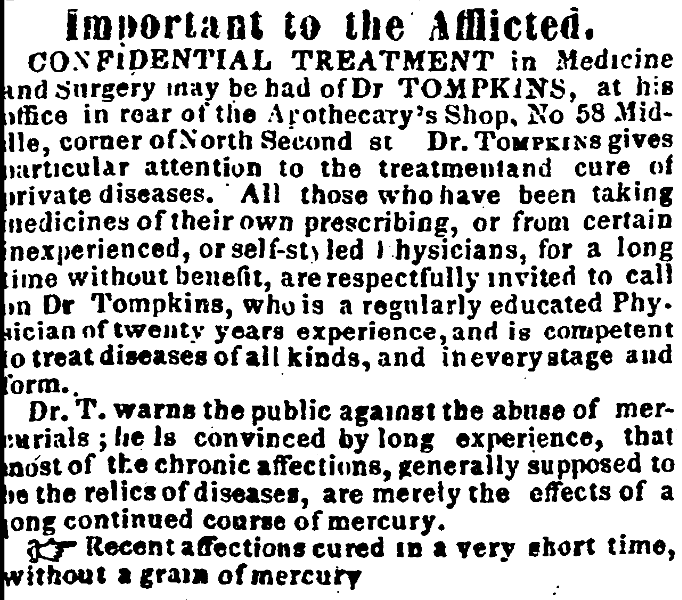

Mercury compounds could also be injected into the urethra. There were doctors who spoke out about the use of mercury in treating syphilis contemporary to when use was at its height. One 1853 advertisement in the New Bedford newspaper the Whaleman’s Shipping List reads,

“Important to the Afflicted

CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT in Medicine and Surgery may be had of Dr. TOMPKINS at his office in rear of the Apothecary’s Shop, No 58 Middle, corner of North Second St Dr. TOMPKINS gives particular attention to the treatment and cure of private diseases. All those who have been taking medicines of their own prescribing, or from certain inexperienced or self-styled physicians, for a long time without benefit, are respectfully invited to call on Dr Tompkins, who is a regularly educated Physician of twenty years experience, and is competent to treat diseases of all kinds, and in every stage and form.

Dr. T. warns the public against the abuse of mercurials; he is convinced by long experience, that most of the chronic affections, generally supposed to be the relics of diseases, are merely the effects of a long continued course of mercury.

Recent affections cured in a very short time, without a grain of mercury”

Even with such objections, mercury compounds still were the standard and did more to sicken their patients than cure them. While whalers were often listed as being off duty due to venereal disease, there was less comment about whether or not they were given anything to attempt to alleviate it compared to other conditions.

“Our mate limping about again—had another furious attact of the venereal He is a used up man I fear,” Mr. Chappell wrote. Ultimately the mate was in a poor enough condition that he left the voyage at the next provision stop they made.

—

Scurvy was another common affliction. Given that whaleships spent extended time at sea and were loathe to waste too much time with anchoring somewhere, fresh food ran low quite often. When whaling in the Atlantic and South Pacific whalers usually fared okay, as there were a fair number of provision stops in locations that had fresh fruits and vegetables readily available for trade. It was on said provision stops that whalers could also, as said by Samuel Wood of the Bowditch, 1849, take a walk to 'knock the scurvey from their bones’.

In seasons that took place up north however, in the North Pacific, Sea of Okhotsk (Kamchatka Sea), Bering Strait, and eventually up into the Arctic, scurvy was extremely prevalent. The fresh food depleted, the ice was always a threat, and unlike other regions there weren't many accessible places to resupply with large amounts of foods that could ward off scurvy. It's in reading journals during these periods that I find the most complaints of scurvy. And sometimes, the more successful the voyage was, the sicker the men would get because they'd spend more time up there rather than giving up and returning south.

The US Consul in Hawaii complained of this in the 1840s, saying:

"Whaleships were much more successful in taking oil on the North West during the last summer and fall than for three or four seasons previous and most of the vessels remained on the fishing grounds much longer than usual, the consequence of which was that many of the crews were severely afflicted with scurvy, some died after reaching port and before they could be landed, while others were carried to the hospital on litters, being too feeble to walk."

There were endless attempts to ward it off. John Martin wrote of men "In the evening, dancing cotillions and jumping the rope to keep off the scurvey". It didn't seem to do much. Within two weeks:

"One man on the sick list, supposed to be caused by his being so long at sea. All hands are complaining of soreness throughout their bodies. If we do not get on shore soon, we may expect to have half the crew down with the scurvey at least. We have no vegetables on board, and are going into King Georges Sound, New Holland [southwest tip of Australia], a place where we can scarcely get anything to recruit with."

His captain allowed the crew unlimited vinegar and free access to the potato pen. The vinegar, a mistaken remedy due to its acidity, wouldn't have helped much. Potatoes are an excellent source of vitamin C, more so when they're raw, but they were rather intolerable to eat in such a way.

William Chappell spoke of a similar struggle with potatoes, and the grim humor the lads maintained to choke them down:

“Three of our men are off duty with the scurvy which makes its appearance in the knees and feet All hands are called aft every morning to get 2 or 3 potatoes apies which they are required to eat raw in the preasance of the officers for fear they may throw them overboard as many require presing invitation to partake of the dainties They have however a considerable sport over them Call them Kodiak Peaches”\

Aside from the crunch of Kodiak Peaches, Dr. King had his own remedy for scurvy as well:

“13. Salts of Lemon

This is good in scurvy when fresh fruit and vegetables can not be obtained. A teaspoonful dissolved in half a pint of water will form an acid nearly the strength of lime juice. It may be mixed with water and taken freely, sweetened or not. [it makes a good substitute for lemonade, in fever, to allay thirst in fever] Water made slightly acidic with it is a good substitute for lemonade to allay thirst in fever."

The Sailor’s Hospital in Lahaina, Maui, constructed in the early 1830s.

—

For all the varying attempts to hold off sickness, it took root among crews nearly every voyage. J.E. Haviland of the Baltic, in the early 1850s spent the last few dozen pages of his journal in a state of declining health and low spirits.

“My side and breast pain me nearly all times I have not been on deck since I came below. The Captain and Mr Stivers are both very kind and come down to see me as often as once a day and sometimes two or 3 times. I am taking medicine but it does not seem to do much good but I think I am better than I was at first. Dear mother how I do wish I could see you once more. I get so homesick and I know I am peevish and cross. Some days I cannot get out of my bunk at all. I blame the captain (wrongfully I know) thinking he does not give me the right medicine but it is a very bad place to be sick at sea.”

He suspected it was due to the harsh conditions of whaling up North, but also held a fear within him that it might be something more serious that couldn’t be remedied simply by warmer climes.

“Dear mother, I shall be obliged to leave the ship when we arive at the Sanwich Islands for I do not think I could live doing another season in the cold Norwest. My cough seems to increase and the pain in my side gets no better I am getting weaker each day and am getting very thin in flesh. I have said nothing as yet to the old man about my leaving at the island as I do not know as he will be willing that I should; but I intend going to a doctor and in all probability will tell the old man I am not fit to go North in the ship […] I would like very much to be in the states now for I am afraid this will turn out to be the Consumption that I have. I think if I could have good medical advice I might get rid of it before it got seated upon my lungs. I am afraid it will be a long before I shall see my native land again.”

Ultimately Haviland is discharged from the ship because of his sickness and is left at the Sailor’s Hospital in Lahaina. His stay seems to do him well. His last entry reads:

“I have been here now going on two months and am entirely free from my cough and think I feel as well as ever again. It is intensely hot and I am heartily sick of the place and sincerely wish I could get away but I do not expect any chance before next fall.”

Unfortunately from here he completely drops off the record, so it’s unknown if he ever made it back home. Like so many of these men, he slips through the cracks of documented history. It’s only through their journals, preserved by chance, that their voices and challenges and feelings are known. Often a whaling voyage marked at least one death due to disease or injury. But many also recovered, sometimes rather miraculously given the circumstances and extent of their ailments. In the face of the conditions of a whaler and the limitations of care both in terms of resources and medical understandings at the time, I’m always surprised that there wasn’t more death. People did what they could, with the knowledge they had.

But as so many people expressed while laid up in their bunks: it’s a hard time to be sick at sea.