One of the things that draws me deeply into whaling history and informed how I shaped the characters in Going to Weather were all of the different reasons that brought men into this watery world. As we begin to meet the lads who will be embarking on this long journey, this blog post can provide some context for who whalers were and why they took up the work.

Regarding the demographics of American whaleships, crews skewed quite young. It wasn’t too common to see someone over the age of 30 who was not a captain/officer or in a specialized role like cook, cooper, etc. Most hands before the mast were between the ages of 16-28, with many in the 20-22 range. Whaling was also more racially and ethnically diverse than many other industries in 19th century America. In the first half of the 19th century around 20%-40% of a crew were Black and African American sailors, and Indigenous people—Wampanoag, Pequot, Shinnecock—would also find work on commercial whaleships. As a voyage went on, ships would also pick up folks from other regions as well such as the Azores, Cape Verde, Chile, Peru, Japan (in the later half of the 19th c) and numerous islands in the Pacific such as Hawaii, Tahiti, the Marquesas, the Marshall Islands, the Cook Islands. This was often to replace crew members who had died / were discharged / deserted—whaleships had incredibly high desertion rates. So those are the demographics we’re looking at when thinking about why someone might go whaling. Very young men, from a number of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Members of the crew of the bark Charles W. Morgan posing with an accordion. Photographed by Pardon B. Gifford, 1906. From the New Bedford Whaling Museum collections.

The specifics of what drew them and how the industry was perceived across all these different experiences varied greatly.

One reason was ‘character building’. It was a way to shape & prove one’s masculinity in an entirely male space that involved hunting the planet’s largest mammals. It was thought to be an adventurous vocation that gave someone the rare opportunity to leave their hometown and see the world. Agents tended to play up that sense of adventure when recruiting. It was also not uncommon for runaways to sign aboard a whaler—it was pretty easy to join one and pretty hard to be brought back once it sailed. There are also a few instances of agents using coercive/conning methods to ship men aboard, but that often wasn’t necessary to fill out crews. This sort of rite of passage into manhood, and striking out on one’s own into the world for the first time was a pretty common one. Whaling was an accessible way to do this in the Northeastern US. At whaling’s peak in the 1840s and 50s, about 50% of every crew in a voyage leaving New Bedford was composed of lads who were completely new to the work and the sea in general.

Sometimes there was a religious aspect to that ‘character building’ as well, a romanticism with the ocean and the ability to see the Sublime there. That if one wanted to see the works of God, the sea was the place to do it. Sometimes men would sign up for ships (or be signed up for ships by their family) known for having Pious Captains and No Alcohol with the idea that the experience would strengthen their moral character. Other men signed on as if they were doing penance for some secret wrong they committed, such as greenhand Elias Trotter, who claimed he signed aboard a whaler because ashore he had committed a ‘sin’ in ‘a manner unparalleled’ and he felt that a whaleship would morally ‘revolutionize’ his life. William Stetson wryly remarked on this notion however, on a different voyage, saying ‘for scarcely a more immoral school than a whale ship can be imagined’.

Another big reason was economics. Some mistakenly viewed whaling as a way to Get Rich Quick (like a nautical Gold Rush), as evidenced by New Bedford having one of the highest numbers of millionaires per capita in the WORLD during its heyday in the 1850s—but that money largely only made its way to agents and shipowners, not the people actually working on the ships. But if one’s lot ashore wasn’t great, on the most basic level going whaling meant guaranteed food and housing for 3-4 years if one survived them. Not to say it was good food or housing by any means, but depending on one’s circumstance that would absolutely be a motivator. And, while the pay wasn’t great and there was a dramatic difference between the cut a mate got and the cut a greenhand got, there was also a strange sort of equity to it. Everyone was bound to the success of the voyage, from cabin boy to captain. Everyone within each specific rank got the same cut, regardless of who they were as men. There were no wages, there was only a share. Which, ultimately led to an exploitative and predatory industry, while also bringing an equalizing element to each man that required perhaps more cooperation with each other than in other trades. What a messy thing!

Two men mincing blubber photographed by William H. Tripp, 1925. From the New Bedford Whaling Museum collections.

But the work was miserable enough that those who had the option to leave the industry after a voyage and choose a different vocation (e.g. white men) often would. Many surviving journals, (most written by white seamen) express an abject hatred for the work and regret for signing on. While there were individuals who came from whaling families who would rise through the ranks to officers and captains, the sons of captains who’d start out as cabin boys with their lives mapped out for them aboard a vessel, there weren’t a lot of ‘career’ whalemen and there was a huge rate of turnover (and even many of those mates and captains wrote about how miserable they were on the job).

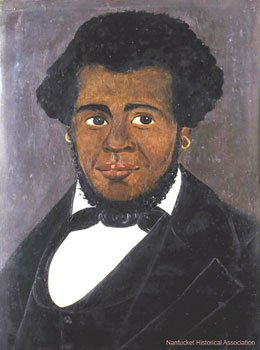

However, for people of color working in the industry, particularly Black men, the idea of being a ‘career whalemen’ came from a different place. A whaleship having a diverse crew didn’t mean it was without the individual racial prejudices of other shipmates, but at the same time, the ultimate determining factor of rank and respect on a whaleship was ‘are you good at hunting whales’. In the antebellum US where for many Black people there were few options for upward mobility in work, where slavery was legal in numerous states, where the Fugitive Slave Act destabilized any sense of security one might have in free states still steeped in de facto segregation, whaling was a viable option. There were no whaling ports south of the Mason-Dixon line, signifying the unique position (and sometimes refuge) that whaling existed in for Black and African American sailors. Unlike white seamen who often left after one voyage, because of the restrictive circumstances of life in the States ashore, Black and Indigenous seamen were sometimes more likely to become career whalemen. This, of course, wouldn’t have been true if more white men stuck with the industry—their unwillingness to stay in the job and rise to the rank of officer created openings in the position for people of color, but again that was because the options were so limited otherwise. Again, what a messy thing!

Absalom Boston, a career whaleman who became captain of the “Industry,” in 1822 with an entire crew of Black mariners.

Indigenous whaleman in New England also saw a substantial opportunity in commercial whaling that brought with it more economic agency than the work often open to them ashore, as well as upward mobility and respect of rank. The few recorded words of native men who found themselves in a place of authority on whaleships, as mates or captains, showed a strong sense of pride in their work and what they built for themselves. Nancy Shoemaker wrote an excellent book on these men and the ever changing contingencies of race they encountered depending on the spheres they found themselves in, called Native American Whalemen and the World, which I highly recommend.

Amos Haskins, a Wampanoag man who was Captain of the “Massasoit”, 1851-53

There is also some scant historical information about this when it comes to people indigenous to the Pacific Islands. British missionary Charles Pitman, who was stationed on Rarotonga in the 1840s and 50s claimed that 100 young men left the island for whaleships in 1849 alone, saying of their $30-$80 advance for signing on ‘these sums according to their custom they soon divided among their friends, and some of them immediately shipped again, not liking to settle down on their own lands.’ Some chiefs forbid young men from going whaling, but when that happened there are instances of the men sneaking to the ship in a canoe and signing on anyway. While the personal voices of these men go unrecorded and their motivations are only referenced through the words of missionaries, it could be inferred that many of the reasons for going were the same: adventure and something new, leaving repressive conditions ashore as missionaries made their presence and control more felt, the potential for greater economic opportunity, etc.

A number of boatsteerers (the people who would throw the harpoon and functioned as petty officers) were men of color. There are also a number of instances of those men who rose through the ranks to become captains. Skip Finley personally identified 50 of these captains and their histories, with the acknowledgement that there were likely more, in his book Whaling Captains of Color. But for those 50, there are many many others who did not find that upward mobility.

Crew members from the Sunbeam and the Eleanor B. Conwell socializing. Photographed by Clifford W. Ashley, 1904. From the New Bedford Whaling Museum Collections.

In short: Adventure and personal development, 2. Economics, 3. Trying to find agency/upward mobility were some of the most common reasons for whaling, depending on one’s background. But few people found those things aboard. It was hard work, dangerous work, and often did not come with any reward.

On this subject, Rites and Passages by Margaret S. Creighton is one of my absolute favorite whaling history books that dives really deeply into the social life and motivations around whaling (with the acknowledgement that most personal whaling memoirs and journals that survive were written by white Americans, so that’s the perspective mostly known and represented)