Content note: This blog post features descriptions and old photographs of whales being processed, which might be graphic for some readers.

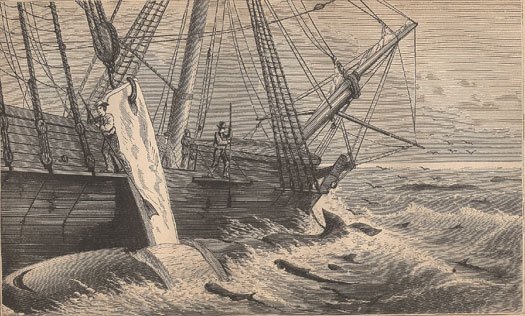

A whaler trying out.

A whale being killed was just the beginning of the labor a crew would have to perform. Provided the carcass didn’t sink immediately thus rendering it all for naught (a thing that happened fairly frequently) it’d first have to be rowed back to the ship.

A whaleboat that, unencumbered could reach a top speed of 5-6 miles per hour, slowed to a painful ½ mile an hour when hauling a 50 ton carcass behind them. The ship would often sail closer to the boats, but there were instances when a boat was dragged so far the ship was no longer visible. So, after taking hours to hunt a whale, it would then take several more hours to get back on board. It wasn’t unusual for whalers to spend an entire day out on the water and return well after dark, exhausted and hungry. But there would be little rest after the return.

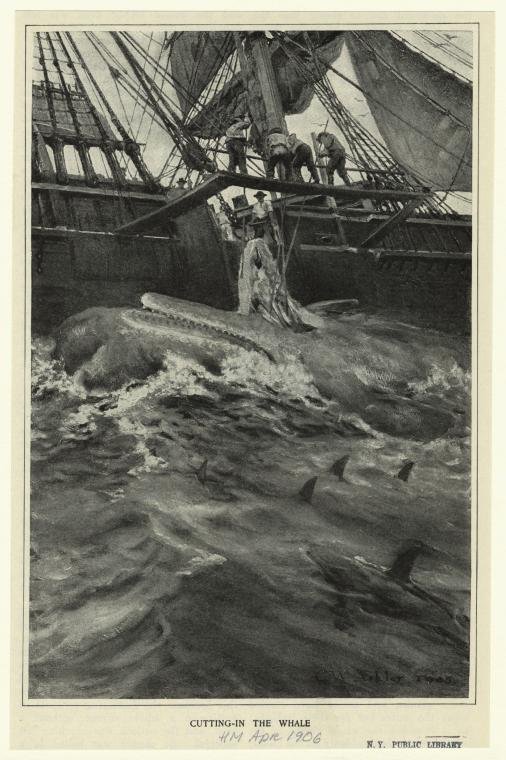

The whale would never be physically brought onto the ship, barring the head if it was small enough. Instead, it was lashed alongside with heavy chains around the flukes and, later, the head. In the first half of the 19th century, narrow planks were hung over the bulwarks and a few men stood upon them over the whale. By the latter half of the century, a more extensive wooden cutting stage would be outrigged on the side of the ship and men step out onto that.

A whale being cut in would be attended by flocks of seabirds above and sharks below, all drawn to the carcass and frantically trying to tear away their share. Boatsteerer William Tripp commented on them while aboard the schooner John R. Manta, that operated in the last leg of the industry in the early 20th century. For many years he photographed his experiences aboard whalers.

“Mother Carey's Chickens by the hundreds are attracted to the ship by tiny bits of floating blubber on which they feed…these little seabirds were our constant companions. They feed on scraps of blubber that float off when the schooner is cutting-in a whale. The superstitious seamen say they are the spirits of drowned sailors…Sharks abound in great numbers when a whale is being cut-in. They are attracted by the large amount of blood in the sea.”

Using spades, whalers would cut a strip of blubber off the carcass. It’d be attached to a huge hook that was part of the cutting tackle that would be hauled up by men aboard at the windlass. As the whale’s body turned in the water, the men on the cutting stage would cut the blubber free. It’s been likened by a lot of people to peeling an orange. This was a dangerous operation; if anyone were to lose their footing either from the stage or in the process of attaching the blubber hook or chains, they could very well be crushed between the whale and the ship. Greenhand Graham Lee aboard the Nimrod, 1840s, spoke of one such instance where the Captain was narrowly spared such a death.

“Commenced cutting after breakfast & finished by 4pm. The Captain came near losing his life by falling overboard between the whale & ship. As it was he escaped with a badly bruised face.”

A man goes down onto a dead whale to retrieve a blubber hook. Photographed by Clifford Ashley, 1904. Via the NBWM.

Adding to individual bodily hazard while precariously balanced over a rolling carcass in shark-filled waters, the weight of the whale could absolutely imperil the ship if the balance shifted the wrong way. As such, cutting in was done as quickly as possible, through all kinds of weather unless the seas were too rough to manage. In that instance whalers spent the night in anxiety, wondering if the hulk of the whale or the violence of the sea would lead them all to founder. Mary Brewster, joining her husband aboard the Tiger in the 1840s described such a night:

“Did not sleep scarcely an hour through the night. The ship lay very uneasy owing to a bad sea and the whale which prevented having sail out. Mr. Brewster up nearly all night. Ship plunged her stearn so heavily I was fearful that it would stove in. Several efforts was made to have the ship lay easy but all was of no use.”

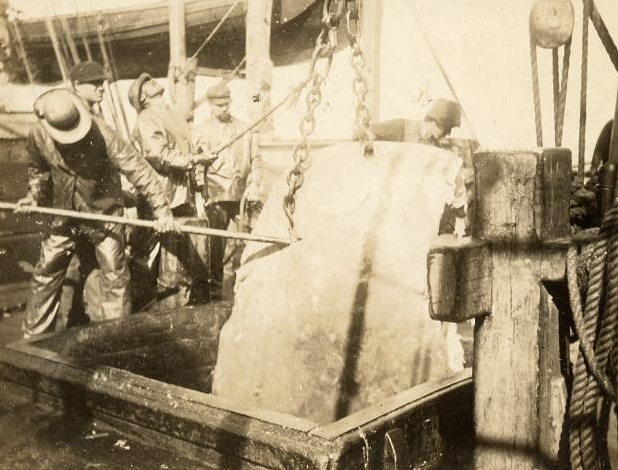

A blanket piece being boarded on the John R. Manta, 1920s. Via the NBWM.

The first strips of blubber cut from the whale were called blanket pieces. Each blanket piece could be up to 20 feet long and it’d hazardously follow the roll of the ship and slide across the deck as it was brought up and cut by a mate who was standing by at the bulwarks with a cry of “Board ho!”. My unhappy friend Benjamin Boodry on the Arnolda, 1850s, had a misfortune with this one time, writing:

“I got knocked overboard by a blanket peace[sic] and have got a lame arm and knee that makes it hard.”

He came out of it lucky though, as getting killed by a giant sheet of blubber was always a risk on the job.

“Captain Brown was killed by the falling of a blanket piece from aloft,” the Whaleman’s Shipping List reported in December, 1853. “He was engaged in cutting in at the time and died within 15 minutes after being struck.”

Whaling wife Elizabeth Waldron aboard the Bowditch also made note of this in her journal as well after speaking firsthand with the crew of that ship.

“Spoke ship Ontario and heard the sad news of Capt. Brown’s death, he was killed that morning when cutting in a whale, crushed to death with a piece of the blubber…Poor man.

The jaw was separated from the head, and the head would be removed and hauled on board with chains to be processed if it was small enough. This involved cutting out the whalebone if it was a baleen whale, or bailing out spermaceti if it was a sperm whale. If the head was too big to be boarded, it’d be hauled up with chains alongside and men would step out onto it to bail spermaceti out of the case.

The messy job of scraping whalebone also had its risk of injury. William Stetson of the Arab, 1850s, spoke of drawing blood with the metal scraper.

“This was a new occupation for us and as all were novices at the trade they did not progress very rapidly the first scrape which I made the skin was scraped from my thumb nearly the whole length of it but the operation soon became familiar.”

As the head was being managed, the blanket pieces would be lowered below decks to the blubber room to be cut into smaller chunks (horse pieces) that were around 6 feet long. During my visit to the Charles W. Morgan, it was the blubber room that made me realize the true reality of this work. Dark and cramped, with a ceiling so low I couldn’t stand up straight in some places. Adding, with imagination, the heat of the tryworks radiating down from above, the slickness of oil covering the deck, the constant pitch of the ship, all while wielding large boarding knives and blubber spades brought home the discomfort of this working environment.

As Melville wrote in Moby-Dick,

“This spade is sharp as hone can make it; the spademan’s feet are shoeless, the thing he stands on will sometimes irresistibly slide away from him like a sledge. If he cuts off one of his own toes, or one of his assistants' would you be very much astonished? Toes are scarce among veteran blubber-room men.”

William Chappell, cooper aboard the Saratoga in the 1850s was spared the messiness of this work as he was busily engaged in preparing casks for the oil. However, he remarked on the dangers of working in the blubber room, with the added stresses of a physically aggressive captain.

“August 16 - The watch employed in boiling. The Captn turned out cross but got over it as soon as he rope ended two of the blubberroom men for being a few minutes behind the times after breakfast If he knew how I detested such an inhumanely disgraceful practice he would certainly desist if he had no higher motive. The poor fellows hurried down in the blubber room out of his way and Shorty one of them soon cut his foot badly with a spade. I dare not tell what the Captn said when he was told of it but he dressed it as well as he could.

August 17 - During the night the George Gardener Alias Portuguese cut his foot with a spade in the blubberroom this as a second time this season. He fainted away. The Captn dressed the wound. Shorty cut his yesterday.”

Once the horse pieces were cut, they’d be pitched back on deck to be minced smaller still into what were colloquially called bible leaves. Upon a wooden plank lashed to the bulwarks, the blubber was sliced in thin leaves so it looked like the bound pages of a book, allowing it to render down in the tryworks easier.

Foremast hands on the John R. Manta mincing bible leaves. Photographed by William Tripp 1925. Via NBWM.

The dried skins left over—the ‘cracklings’ as it were—would then be tossed into the trywork’s fires to fuel them, “Like a plethoric burning martyr, or a self-consuming misanthrope, once ignited, the whale supplies his own fuel and burns by his own body,” as Melville wrote.

The heated oil would be bailed out of the tryworks with a dipper into a copper cooling tank located beside it, before ultimately being transferred into casks. Again, a task not without danger. It wasn’t uncommon for someone to be burned by oil or find themselves injured or even killed by a runaway or falling cask. In at least one instance (which I’ve tried and failed to find…it was in one of the many journals I read…you’ll just have to trust me, sorry!) the oil wasn’t given adequate time to cool, resulting in it bursting from one of the sealed casks and splattering hot oil upon a few unfortunate men.

A man pitches hot oil with a dipper into the cooling tank. Photographed by Tripp. NBWM.

It was grueling and nightmarish work. A whaleship trying out could be smelled for miles by other ships before ever being seen on the horizon, to the point that they were very much considered pariah ships by merchant and navy vessels, best avoided. John Ross Browne on his 1840s whaling voyage described the scene of a ship cutting as having “a murderous appearance about the blood-stained decks, and the huge masses of blubber lying here and there.” Microbes on the whale’s skin & blubber could cause skin reactions and boils where it touched, which could be what doctor John B. King was alluding to on the ship Aurora, 1837, when he mentioned “persons have biles to break out in different places and continue for a long time, as is often the case in whale ships”. In addition to cutting blubber, men would fully climb into the decapitated head of a sperm whale to bail out the spermaceti there by hand as it wasn’t rendered down like everything else, drenching their bodies in the coagulated stuff. Before the carcass of a sperm whale was cut loose, the bowels were sometimes searched for ambergris as well. Whalers called the mess of oil and gore that sloshed around the deck ‘gurry’, and it truly got everywhere and into everything. The scuppers were plugged to keep it from sliding into the sea, and small blocks of blubber called ‘nippers’ were blotted on the deck by whalers to catch up every stray bit because that was money at the end of it all. The oil permeated everything, including men’s own dreams. William Abbe of the Atkins Adams, 1850s, wrote,

“To turn out at midnight and put on clothes soaked in raw oil. To go on deck and work for Eighteen hours among blubber—slipping + stumbling on the sloppy decks til you are covered from crown to heel with oil—eating with oily hands oily grub—drinking from oily pots til your mouth and lips have a nauseating oily luster—turning in for a few hours sleep — after wiping off your bare body with oakum to take off the thickest of the oil + then to dream you are under piles of blubber that are heaping + falling upon you until you wake up with a suffocating sense of fear + agony only to hear the eternal clank of the cutting machine and the roar of the fires under the tryworks or the wind dismally howling through the rigging — to fall asleep only to dream again til you are called on deck.”

Men standing up to their knees in blubber, via the NBMW.

Women accompanying their husbands aboard also found the work infiltrating their domain. Mary Brewster wrote,

“I just begin to see some of the beauties of a whaleman’s life, dirt and grease all the go. I keep below nearly all the time in my room as the decks are getting rather soiled and the try-smoke very disagreeable to my olfactory senses.”

Azubah Cash, on the Columbia, 1850s, was more actively involved in watching the crew.

“I have felt very bad and have been seasick some, have done no work to day. After I eat a little supper I went up far as the gangway to see them cutting up the head. It was curious enough and greasy enough too. We cannot report ourships [written over ‘ourselves’] clean now and I do not believe she will be very soon for the oil has run between decks as far as the dining room, I hope it will not get in here.”

At one point Azubah’s 10 year old son, Alexander, also jumped into part of the work, “darting an iron that he fixed into the sharks as they come side of the whale.”

All told, the cutting and boiling process tended to take a couple days. Graham Lee described the toll it took on the men:

“July 13th Boiling & stowing down. Sail in sight. Lay in all last night sick for want of sleep. The constant work has about used up the crew.

July 14th Stowing and boiling. Finished trying. Three sails but no whales in sight. Mr. Smalley wanted to hoist the colors today, being the first time that all hands were on deck, some being sick all the time. Last night one of the hands fainted in the blubber room fairly worn out by fatigue. This is the second occurrence of the kind.”

J.E. Haviland of the Baltic, 1850s, also described the wearying demands of the work in a series of journal entries:

“Tues 23rd I never felt so sore + stiff as I did this morning my arms are so I cannot raise them up to my head. It is my business when cutting in a whale to attend the falls + yesterday they were so wet + greasy that they would take me up to the windlass by the run. The Old Man tried to assist me but their was no use around would go the fall + down go the blanket piece nearly hauling our arms off. Built a fire under the works this morning at 6am now busy trying out and cutting the bone from the head +c. You cannot imagine my Dear Mother how highly we prize a few hours rest + sleep at such times as these.

Fri 26th I could not be any more stiff + sore than I am + that is the general complaint with all hands. All done trying out + have stowed down all the oil the whale stowed down 170 bbls. All hands on deck again today no sleep for our watch since 2 o clock last night only about 10 hours rest out of 48”

Men scrape whalebone. Photographed in 1887 by Herbert Aldrich. NBWM.

Still, whaling wife Mary Lawrence on the Addison saw the relief that fell upon the crew at getting a whale.

“A change has come over the countenances of our ship’s company. Notwithstanding that they were up all night cutting in, faces long unused to smiles are radiant with pleasure, a sight that delights me very much. Minnie [her young daughter] was so interested that she awoke very often through the night to enquire what progress they were making and if I was sure they would save him all.”

After all was done, and cleanliness was restored to the ship, whalers were allowed a brief moment of contentment. As Haviland wrote after his days of labor,

“Sat 27th I feel much better to day I have given myself a good wash + a clean shave + got in all clean clothes. You would not have known your own son if you could have seen him yesterday. I was nearly black with smoke + dirt. (with shame) I say it was the accumulation of 2 months dirt + 4 months beard. Everything looks as clean + bright as it did before we took the whale tho Old Man says 6 more like this and straight for New Bedford we steer.”

For all the grime, exhaustion, and risk of the work, in the eyes of the whalers it was preferable to the monotony of an unsuccessful voyage. Each whale taken, each hour of greasy dangerous work, was one step closer to a return home.

Whalers by JMW Turner, 1845.