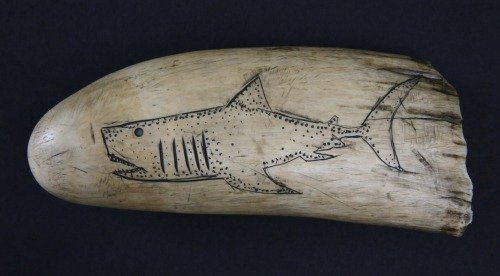

I think scrimshaw is one of the most fascinating material goods to emerge from the history of the American whaling industry (which is the context I’m discussing here, though of course the artform exists across numerous eras and cultures outside this brief blip of nautical history). Apologies for the lack of sources on these images—they all came from assorted auction listings over the years rather than any documented museum collections. They all live in private collections somewhere.

Scrimshaw is one way to see amateur art that doesn’t often survive in other forms. To see the art project of an ordinary man who was bored and needed something to do with his hands. Others were highly skilled craftsman, creating intricate engravings or mechanically expert tools. The most common scrimshaw was etched on sperm whale teeth. Sometimes those images came from the maker’s own imagination and sometimes they were copied illustrations. Ships & whaling scenes, women, mythical figures, and patriotic symbols make up the bulk of the visual language in those pieces that survive.

But alongside the teeth were all a manner of carved items: canes, candle holders, pie crimpers, children’s toys, sewing boxes, yarn swifts, corset busks. So much bone fashioned into quiet little homegoods. And it’s that contradiction within scrimshaw that fascinates me. The brutality of the industry, this ivory from an animal that frankly died terribly, that’s then softened into a little domestic item. An object that could have hours to years of work put into it. Some were made to be sold but many were made as gifts. In the long stretches of boredom at sea, in the lull between back-breaking work and life-threatening terror, scrimshaw gives a window into where the minds of these men continually turned. It shows where their hearts were and what they were holding on to over all the years they spent adrift in saltwater and blood and oil. That’s the poetry I see in scrimshaw. Pain and love and longing and creativity and playfulness all bound together in these complicated little pieces that found their way out of the hands of their anonymous makers to preserve a small part of their story.

Some scrimshanders names are known. Frederick Myrick is one such American whaler. His name is known not so much for the scope of his life (of which little is known) but for his scrimshaw. Born in Nantucket in 1808, he first went whaling in 1825 on the Columbus and then again on the Susan 1826-29. In the last few months aboard the Susan, Myrick engraved over 30 sperm whale teeth, all depicting the ship he was on (though there are a handful that depict other vessels). He signed and dated nearly each one. These pieces are often referred to as ‘Susan’s Teeth’ now, and when one comes up at auction it’s not unusual for it to sell for six figures.

One of Myrick’s teeth showing a whaling bark and whaleboats out on the water. A banner above the ship reads ‘The Susan boiling and killing sperm whales’, and there’s also an American eagle at the tip of the tooth holding a scroll that reads ‘e pluribus unum’

Many of the teeth Myrick scrimshawed included an inscribed couplet of his devising: A dark wish for luck that succinctly gets at the violent and unstable heart of American whaling.

“Death to the living, long life to the killers

Success to sailor’s wives, and greasy luck to whalers”

Sometimes large scenes were etched on panbones as well. This one features copied images made in other mediums connected to the whale fishery, and may have been carved a bit later than the Peak Time for the industry.

A panbone showing whaling scenes etched on a white ground.

Melville’s description of the Pequod, the fictional ship in Moby Dick, was also built on reality as scrimshaw was used to sometimes make not only art pieces but functioning parts of whaleships.

“She was a thing of trophies. A cannibal of a craft, tricking herself forth in the chased bones of her enemies. All round, her unpanelled, open bulwarks were garnished like one continuous jaw, with the long sharp teeth of the sperm whale, inserted there for pins, to fasten her old hempen thews and tendons to. Those thews ran not through base blocks of land wood, but deftly travelled over sheaves of sea-ivory.”

Here are some 19th century double sheave blocks fashioned out of whalebone:

Moving from scrimshaw on teeth and jawbones, pie crimpers are some of the more common sculptural items. Popular motifs included animals (dogs, snakes, and unicorns/hippocampus are big), body parts (mostly clenched fists or lady’s legs), and geometric designs.

Others were more mechanically complicated, such as automatons and children’s toys with moving parts and gears. Here’s one of a small rocking sailboat, perhaps made for someone’s child or younger sibling.

Sometimes a particular creative fellow created something more eccentric, like this wild writing desk kit fashioned out of a carved panbone and sperm whale teeth. I love his idea of adding little bone flukes to the natural curve of the teeth to create a whale’s tail from them.

Another frequently scrimshawed object was a corset busk that would be slid into the front of the garment in order to maintain the posture. A rather private item compared to others. And one with a very on-the-nose message of wearing close to one’s heart the memory of someone who’d be gone for 3-4 years, who might never come home again. On some level, so many of these daily objects whispered ‘forget me not’, ‘think of me while I’m gone’.

A busk with a portrait of a woman and a ship engraved on it. It reads ‘To my Beloved Lydia. 1843. Whilst ye set this busk on thee pray do think of me. H.L.’

There’s something tender to all the various domestic items that were fashioned on the job so long and far from home, but it’s the yarn swifts that really captivate me. They were one of the most complicated pieces of scrimshaw to make, with over one hundred different pieces that would have to be carved. It could take someone the length of the voyage (2-4 years) to complete a single one. Unlike teeth which were comparatively quick to make and were frequently intended to be sold, it’s very unlikely that a swift was made with the aim of selling it because of the significant labor that went into it. They were almost certainly all gifts, and very special ones at that. Every time I see one I can just feel the love towards its intended recipient radiating off of it.

An elegant yarn swift held together with pink ribbons, on a wooden base inlaid with more whalebone.

Scrimshaw captures a specific snapshot of a moment in time. On a broader scale it’s a surviving reminder of a bloody industry that flared up and winked out, preserved in the form of a long-lost ship and the spout of a long-dead whale inked on a yellowing tooth. But that snapshot also reveals the emotional world of the men who were caught up in such an industry: what they valued, what they thought about, what they missed, and what they wanted to be remembered of them.